Back in July the Queensland Government released its Housing 2020 strategy, setting the direction for the social housing system over the next seven years. The headline action is the transfer of management of 90% of Queensland’s social housing to non-profit providers by 2020, with the creation of eight to ten large-scale non-profit providers.

The bold scope of this change has tended to deflect attention from other aspects of the strategy, but there is something else here that is of crucial importance to tenants. On Page 6 of the strategy there is a table called ‘The Path Forward’ with two columns. The first is headed ‘The old: Features of Queensland’s old social housing system’ while the second is ‘The new: Features of a flexible, efficient and responsive housing assistance system’. The very first item on this table lists the feature of ‘the old’ as ‘a view that social housing is a home for life’ and ‘the new’ as ‘greater emphasis on social housing as a transitional period on the path to private rental or home ownership’.

This is a change that has actually been coming for a while. Since 2005, new Queensland social housing tenants have been signed up on a ‘duration of need’ basis, with most tenants granted four-year leases with a review of eligibility at the end. The incoming government shortened this to three years. However, it is a long time since a government stated this aim so strongly, or referred so clearly to the private rental market as a destination for social housing tenants.

Rationing

This change is all about rationing. More than 20,000 households are waiting for social housing in Queensland, many of them in dire circumstances. It’s understandable that the government would want to do all it can to house them. However, this policy direction also shines a light on the other sectors, and particularly the private rental sector. How well is this sector able to meet the housing needs of low income households?

Affordability

The first issue with private rental is its affordability. The National Housing Supply Council reports that in 2009-10, 60% of low income rental households – over half a million households – were paying over 30% of their income in rent and over 200,000 households were paying over 50%. This doesn’t suggest a lot of hope for those departing social housing for the private sector.

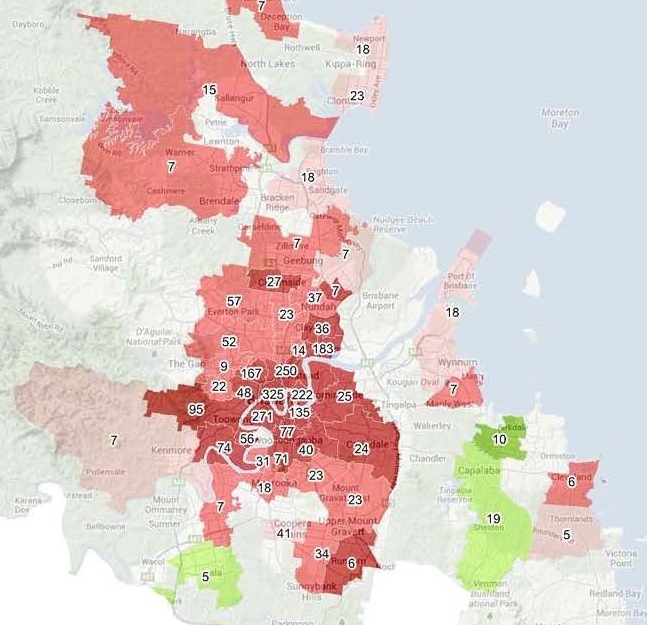

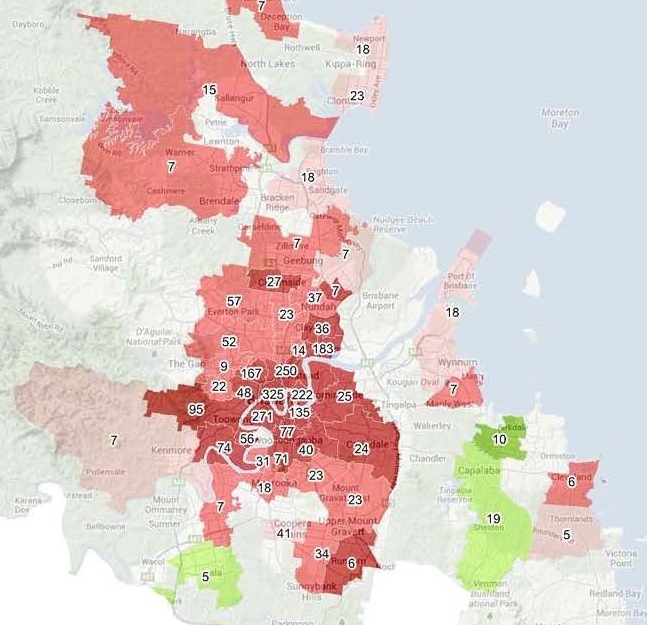

Some work we’ve been doing recently for a local client bears this out. They asked us to report on affordable locations in which to settle low income refugees in the Brisbane, Redland and Moreton local government areas. The answer for many households is that there are no affordable locations. For a single person on Newstart allowance, for instance, there are five suburbs in this entire area where the median rent on a one-bedroom unit is less than 40% of their income, and these are outer suburbs where one-bedroom units are rare as hens’ teeth. The only way these clients can afford to rent is by sharing.

Other Issues

However, affordability is only part of the picture. In the July 2013 joint edition of Parity and HousingWorks, Greg Budworth (CEO of Compass Housing Services in NSW) provides an insightful comparison between social housing and private rental. He analyses 24 aspects of housing management under the headings of tenant obligations, tenant rights, landlord powers, landlord duties, application processes and other issues like appeal rights, tenant engagement and quality assurance.

Of the 24 factors he analyses, seven are much the same for both sectors, and on the other 17 tenants are clearly better off in social housing. They have better access (only needing to make one application), more security of tenure, more accountability by their landlord, a greater likelihood that their landlord will work with them to resolve problems and refer them to support services, and much better assurance that their landlord will adhere to good standards of management practice.

We need to do better…

For as long as I can remember, the private rental market has been a backwater of housing policy. Aside from residential tenancies legislation, the market is pretty much left to itself. This works fine for many people, but clearly not for low income households, and particularly not for the highly disadvantaged households who are the main users of the social housing system. If the Queensland Government is serious about the private rental market taking a greater role in housing low income Queenslanders, it might need to take a closer look at how this market is operating.